When the pandemic hit NYC, I was teaching at NYU. It was Jan 27th 2020 when I walked into the AI class that was packed with 60 students. Some were wearing masks and I simply attributed it to their place of origin. During 2007–2012 I was going very frequently to South Korea, China and Japan and I was very accustomed to the fact that in East Asia, masks are common. Still the number of masked students was higher than I would consider normal and wondered if this is something to do with, at the time, what was happening in China.

One and a half months later, the number of students in the classroom had fallen to a handful — everyone was wearing masks and I was uncertain what would happen next. Few days later I was playing with my new document camera that NYU had sent me at home and started having my own symptoms. Recovering was relatively speedy for both me and my spouse although smell and taste took several weeks to return. I missed just one or two classes and wanting to see what the students can do in a project setting relatively affiliated with what we were all experiencing I gave the 3rd and last project in that class titled “Going Back to Work”.

Below you can read the class project description at the time.

Going Back to Work

In the spring of 2020 the world has experienced an unprecedented in modern history event - a pandemic that killed tens of thousands of people and resulted in a global economic recession; tens of millions lost their jobs. You are called to help rebuild the economy and develop an system that can protect people from infection while still allow them to go back to work.

One of the ways that this can be achieved is by maintaining a certain density of people in buildings. To do that, we need to engineer a reservation (booking) system where each user uses a messaging app to reserve a time slot (period) that he or she is allowed in the building, by entering the destination address and desired arrival time and length of stay.

Your AI-powered decision system responds giving the requestor a decision. Each decision is either an accept, manifested with a QR code with the address and allowed arrival and departure times in text or a downright reject. The departure time is needed since the system must preserve building density and people must leave the building to make “space” for others to enter. The security personnel or receptionists supervise a programmable scanner or manually scan the QR code to allow entrance and exit (pretty similar to the scanners used to allow entry of an aircraft at the gate). The system also allows for group bookings, made by an assistant for example, to enable face to face meetings. In this case the decision system accepts or rejects for the whole group.

To give you a practical perspective, the system can be entirely powered by well known chat / messaging apps and your cloud-native & cloud-hosted application - the decision system. The system also complements contact-tracing systems that are powered by mobile OS and are under active development by Apple and Google.

To simplify the problem,

- The departure times cannot change dynamically. This means that if the actual demand is lower than the predicted demand when the scheduling decision took place, the departure time stays fixed. Employees / customers can extend their departure by sending another request via the messaging app but this is an independent reservation and is not accounted for the original decision policy.

- Although this can be very useful for stores and co-working spaces, there is no attempt to flatten the demand curve by distributing accepts among geographically separated facilities of the same legal entity.

- There is no semantic consideration in the decision making algorithm. It is assumed that theaters and other sports venues control the reservations and seating to maintain social distancing. The same is assumed for office buildings - the system is not designed (although it can be extended via video surveillance and other localization technologies) to consider per office floor occupancies.

- There are no fairness considerations. One can go ahead and book multiple time slots by sending messages one after the other to the system. This is an important limitation but can be easily addressed in practice and will unnecessarily complicate the policy given the limited time to complete the project.

- There are no risk considerations in the decision making process. A user that requests a reservation that lives far away and travels via public transportation has equal chances to a user that lives next to the requested address.

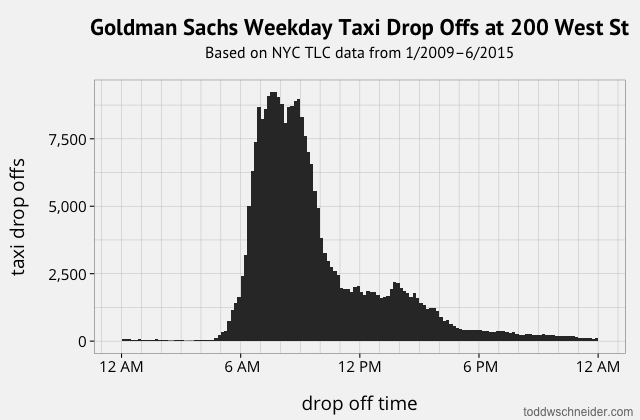

This system can be powered by cellular network based localization datasets but in the absence of such data that only operators possess, we will use the the dataset that contains all NYC taxi rides from 2009 to 2019. The dataset includes pickups and drop offs and we will focus for this problem on drop offs only and only in the borough of Manhattan (if you face computational load hardships you can focus on the midtown Manhattan area only).

There are two steps to do:

- Preprocessing step. In this step you generate the demand model before the intervention by the decision making process. Think about it as the pre-pandemic demand for the address. You need to take the (lat, long) drop off data and using a geocoder convert them to addresses. See also here for some preprocessing ideas and here for code that does preprocessing. Below is a sample result of the preprocessing mapping the drop off data into addresses.

- Optimal Decision Policy. You will use the demand model from (1) as input to simulate the requested reservations at a location. Obviously the optimal policy will involve a closed loop feedback where the actual arrivals into each building are streamed in almost real time to the web service such as from video surveillance cameras. You are free to make assumptions in determining the policy such as knowing the actual capacity of each of the addresses / neighborhoods you are demonstrating. As an example, the decision policy can be a scheduling policy. The scheduler at any instant in time determines whether to accept or reject incoming reservations requests.

The project is flexible in the sense that there is not a strict metric other than a demonstration that the policy flattened the demand curve at a location (such as the GS building above). I hope you enjoy doing it not only for its technical depth but also because it serves a real and timely need with worldwide impact.